Ron O' Neill was 11 years old when an explosive killed three boys and injured ten children, including himself, on a trip to the Wicklow mountains on April 14th, 1979

“The next thing I know, was this flash and a bang, and my reaction was to put my arms up in the air to protect my head. And then it was just total silence.

“I tried to get up off the ground, but I couldn’t get up. And then I caught sight of my legs.

“I seen all the injuries to my legs and was just lying there…waiting".

Ron O'Neill was 11-years-old when he went on a trip with St. Mary's Youth Club in Lucan up to the Glen of Imaal, which were involved in a tragic accident that killed three boys and injured ten children on April 14th, 1979.

The Journal Investigates has released an extensive investigation into the explosion and the aftermath of the tragic incident that occurred on that day in the Glen of Imaal.

Three boys and ten children were injured when an Army shell exploded.

The victims were part of a group from St. Mary’s Youth Club in Lucan who had travelled to the Glen of Imaal for the Easter weekend to hike up Lugnaquilla.

They entered Defence Forces territory along their route, and came across an old tank that was in use at the time as a target.

One of the boys picked up an object, thinking it was part of the tank.

Another boy threw the object against a rock, causing it to explode.

The object thrown was an unexploded 84mm HEAT – High Explosive Anti Tank – shell.

Two boys were killed almost instantly, with a third boy having died later in hospital.

The three boys killed were Declan Kane (13), Derek Finn (13) and Victor Mills (12).

All three were from Sarsfields Park, Lucan.

Speaking publicly on his story was Ron O'Neill, originally from Lucan but now resides in Celbridge, who spoke with The Journal Investigates team.

Ron also spoke on this morning’s Kildare Today show.

He retold what happened on that day on April 14th.

He was only 11 at the time of the incident, and was the youngest person on the trip.

The minimum age allowed to go on this trip was 12 years, but as it was his 12th birthday the following week, he was given permission to go.

He recalled how on that Saturday in 1979, groups were made in order to cross the Knickeen River, with some children and leaders wading through deep water and the rest continuing upstream to cross at a more shallow point.

Ron was in the second group with his friend, and as they walked to re-join the first group, one of the group members threw something which landed between Ron’s legs.

He described it as the head of a giant dart, and it was quickly passed around the group for others to look at.

They stuck it in the ground, which was soft and marshy, and continued on.

They group debated what the object was, until one of the boys took the object and threw it against a rock, leading to an explosion.

“The next thing I know, was this flash and a bang, and my reaction was to put my arms up in the air to protect my head. And then it was just total silence”, said Ron when speaking on Kildare Today.

“I tried to get up off the ground, but I couldn’t get up. And then I caught sight of my legs.

“I seen all the injuries to my legs and was just lying there…waiting.

“Then people started shouting and crying…I didn’t feel any pain at the time. I was just totally, totally numb. All I could hear was the ticking of my watch on my arm”.

One of Ron’s legs was hanging off, and both his knees were severely damaged.

Others in the group who were close to the explosion had similar injuries to Ron, with limbs almost severed.

They would later have to undergo emergency surgery.

Including the deaths of three children, ten children were injured (eight boys and two girls).

Injuries sustained included severed and severely damaged limbs, shattered bones, burning and shrapnel damage.

One boy had his eye hanging out, another badly burnt.

It was revealed that the St. Mary’s Youth Club had entered a no-go zone in the Wicklow mountains.

An extensive search of the area in the following weeks after the explosion revealed another 54 live shells.

Ron recalls the rescue, which took hours due to difficult terrain and inaccessible area.

He was helped by a local rescue team, who checked everyone’s vitals.

An Air Corps helicopter transported two of the worst injured – Gráinne Condron and Richard O’Neill – to St. Vincent’s Hospital, Dublin.

Speaking to the Sunday Press at the time was local doctor Pat McCarthy from Naas, who described the scene as “unbelievable, and worst horror [he had] seen in [his] life”.

Ron, with his leg almost severed, said as team of local doctors administering medical aid wanted to amputate his leg there and then.

However, they put Ron in a vacuum splint, which stopped him from bleeding out and ultimately losing his leg.

Ron, along with other children, including 12-year-old Victor who later died, were first taken to Naas General Hospital but were then transferred to Temple Street in Dublin.

Victims had to undergo emergency surgeries, amputations, and intensive rehabilitation for a variety of injuries they sustained, mostly to the lower parts of their bodies.

Ron suffered damage to his kneecap on his right knee, which had to be put in a cage system to allow the bones fuse back together.

His left leg was broken in three places, and suffered damage to the kneecap.

He spent four months in Temple Street and had to undergo years of rehabilitation.

Newspaper clipping of Ron O'Neill (right) pictured with Brian Malone (left) who was also injured in the explosion. Image via The Journal Investigates, courtesy of Ron O'Neill

From there, he was in and out of Cappagh until professionals felt he was capable of living a “practically normal” life.

Ron says the surgeries are still ongoing to this day.

The mental impact of the accident is something that “will never go away”, Ron said.

“What we saw that day…the images are just imprinted in you and they’re always there. They don’t go away”.

Ron spent his time with another victim, David Reid, and both boys were visited by Brazilian soccer legend Pelé.

Pelé was in Ireland at the time as an Ambassador for Unicef promoting a charity match, and stopped by to visit children in the hospital, including Ron and David.

Following the incident, calls were made for the Glen to be closed, fenced off, or longer be used.

At the time, Robert “Bobby” Molloy was the Minister for Defence, and expressed sympathy for the victims and their families.

He ordered an Army investigation, however the Defence Forces and the minister himself denied to accept liability for what happened on Army land.

Ron further expressed how this accident did not need to happen.

“The warning signs were there beforehand…and the place should’ve been cordoned off or marshalled more thoroughly to avoid anything like that happening again”.

Members of St Mary’s Youth Club took issue with claims that the children weren’t properly supervised, and stated that the group only passed one sign – which warned against entering the Glen if red flags were flying.

During the inquests into the deaths of the three boys, the 22-year-old chairman of St Mary’s Youth Club repeated that as there were no flags flying, he thought it was safe to enter the Glen: “We saw a sign which I stopped to read,” he told the court, according to contemporaneous reports of the time.

This was not the first accident to have occurred, as in September 1978 three boys were injured in a similar explosion in the same area.

On September 1st of that year, the three boys were on a trip with a priest from Dublin.

Unlike what happened several months later in 1979, these boys were warned to stay away from the Glen by the Army.

However, one of the boy sounded the alarm the next day after all three were injured.

According to a report in the Evening Herald, the boys had found a shell and threw it against a rock, injuring all three of them.

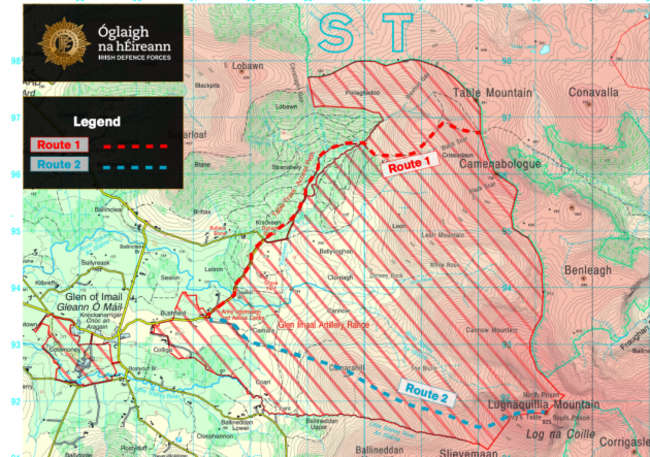

Contemporary map of the Glen of Imaal showing designated walking routes. Image via Defence Forces

The Army artillery and firing range makes up 5,948 acres of the Glen, used by the British forces in 1895 and later the Irish Defence Forces.

Following this accident, the Army committed to erecting more warning notices and writing notices to An Óige – the youth hostel group that owned the Ballinclea hostel – and other youth groups about the dangers in the Glen.

The Army did write to An Óige and other youth groups, but documents confirm no new warning notices were erected between September and the April explosion.

An Irish Independent article from after the April blast claimed that this was the result of a communications breakdown between the Army and the Board of Works, the state’s property and engineering agency (now the Office of Public Works).

45 years on from the accident, survivors continue to live with the physical and mental repercussions of the explosion that killed three boys and injured ten children.

Ron learnt how to manage the effects of the accident, but says despite taking medication, the PTSD never goes away.

“It’s manageable, but it never goes away. The memories never go away, the feelings don’t go away for the hurt that happened to other people and all the other families.

“It was 32 people that went [to the Glen], 29 of us came out and every single one of us would have been affected in some way”.

The Journal Investigates report noted that the story dominated news headlines in the following days and weeks after April 14th, but quickly the victims faded from the media and public view.

The Government paid out compensation following legal battles, but no official apology has been offered to the survivors or their families.

The full investigative report, including declassified military reports, can be found on The Journal Investigates.

The full interview with Ron O'Neill on this morning's Kildare Today show can be listened to here:

Lives At Risk: HSA Forces Closure Of High Risk Construction On Bridge Street Site In Kilcock

Lives At Risk: HSA Forces Closure Of High Risk Construction On Bridge Street Site In Kilcock

260 Children With Additional Needs Still Without School Places As Politicians Begin Summer Break, Says TD

260 Children With Additional Needs Still Without School Places As Politicians Begin Summer Break, Says TD

Council Refutes Claims Of Collecting Migrants From Airport And Offering Preferential Housing Treatment

Council Refutes Claims Of Collecting Migrants From Airport And Offering Preferential Housing Treatment

Victory For Kilcullen: HSE Agrees In Principle To Hand Over Building Restored By Locals To Council

Victory For Kilcullen: HSE Agrees In Principle To Hand Over Building Restored By Locals To Council

Connected Break-Ins Rock Leixlip: Gardaí Probe Early-Morning Crime Spree

Connected Break-Ins Rock Leixlip: Gardaí Probe Early-Morning Crime Spree

Man Punched In Face And Knocked To Ground In Random Attack On Maynooth’s Convent Lane

Man Punched In Face And Knocked To Ground In Random Attack On Maynooth’s Convent Lane

Extraordinary U-Turn Underway As HSE Rethinks Controversial Sale Of Kilcullen Building Restored By Locals

Extraordinary U-Turn Underway As HSE Rethinks Controversial Sale Of Kilcullen Building Restored By Locals

Kildare Man Asks If He Can Claim Ownership Of A Field Because The Owner Has Not Showed Up In Years

Kildare Man Asks If He Can Claim Ownership Of A Field Because The Owner Has Not Showed Up In Years